I never felt beautiful as a child or as a teenager. I never consciously linked these feelings to my race. Like most children growing up in a predominantly white postcode district, my earliest education disposed me to ‘colour blindness’, leaving me ‘blind’ even to my own disadvantages. Collective cultural attitudes in Bexley, including standards of beauty, are rigid and exclude the celebration of people that look like me. My socialisation from birth left me with a very distorted belief system on ‘objective’ definitions of things like funny, beautiful and cool. I accepted at a young age that I was never going to be validated for my looks, consequentially believing that I was objectively undesirable. I associated my non-beautifulness with things like my height, my body shape, my hair texture, but never made the connection between these factors and my skin colour. In primary school, beautiful looked like short, blonde, petit, pale girls with silky hair that everyone wanted to play with. As a mixed-race child, these criteria were unattainable and inherently incompatible with my genetics, but no one told me that. Cross-legged on scratchy carpets, I would resent always having to play the hairdresser because my hair was too thick to be quickly folded into neat plaits.

I would marvel at the silky strands between my fingers, while simultaneously swatting away little boys that would stuff pencils into my curls without me noticing. Strangely, it was me who was incessantly told off by teachers; reminded that I was in a classroom, and not, in fact, a salon. Throughout primary school, for as long as I can remember, I did all I could to conform. However, bending, heating and twisting my hair into little frizzy semi-afro side-ponytails never measured up to hairstyles I saw flaunted and validated in the playground. Still, I never viewed myself as innately different from my white friends, I was truly “blind” to any and all race. My 11-year-old self had sneaking suspicions of my difference, and consequential undesirability, in this area; which, at the time, felt like the entire world. Suspicions that, when voiced, people would do their best to thwart, but never explain.

The move to secondary school turned my suspicions into facts. I was socialised into a community with overt beauty standards, on which many social hierarchies were based. This time, being unable to meet a new set of standards was internalised as a personal failure. My experience of the overt racism we are taught about, hearing the n-word, being told to “go back to my own country”, was minimal. So, much of my oppression took the form of internalised beliefs of myself as inferior, upon which I based my self-image, and self-respect. Vivian Huynh with the Guardian writes that “The biggest trick the devil played was teaching people of colour to be their own oppressors.” That’s what I became. Once again, I assimilated without hesitation. I straightened my hair daily. Then I bleached it. I dieted to thin my thighs and hips, but to no avail. I lightened my skin. First cosmetically, by using the same shades of makeup that my white friends had, and later digitally, with photo editing apps. My relationship with editing apps in secondary school, in hindsight, feels embarrassing but, at the time, felt mandatory. I would make myself shorter, thinner (in the wrong places), larger (in the right places), my hair longer and flatter, my skin paler, my feet smaller, my face more oval. My digital self was easy to manipulate, but in real life, there were constant reminders of my deviation from the criteria of beauty. My 5’4” friends would compare their weight at lunch, while I, at 5’9”, would stay notably silent. Then they would compare their fake tanned arms and legs to mine, exclaiming “I’m almost as dark as you” as if to point out that my ‘tan’ was just over the threshold of desirable. I’d watch the beautiful girls flaunt their bouncy blow-dries or crimped ringlets, and patchy fake tanned legs, while I boasted my chemically relaxed and bleached hair with a face clad in foundation two shades too pale.

None of this is to say that I was never paid a compliment, they were scarce, but never the less existent. Yet, as Frantz Fanon said, “the Negro is appraised in terms of the extent of his assimilation” and I was no exception. I can remember on one occasion I furnaced my hair into submission and then re-curled it using hot rollers, achieving a more Eurocentric curl pattern. I’ve never received more compliments on my hair than when I swapped my natural curls for artificial ones. Other compliments came with clauses, that kept my beautifulness conditional and separate to that of communally celebrated white beauty. On several occasions I was told that I’m “good-looking, for a black girl”, I’ve even heard that I’m “the only good-looking black girl” a boy had ever seen. This othering of my aesthetic validation, at the time, would feel confusingly insulting yet undeniably satiating. I was being told that I was attractive, but only in relation to being able to overcome my inherent ugliness. These comments put asterixis next to my beauty, which I internalised. *Beautiful hair. *When straightened. **Beautiful face. **Despite brown skin.

Suddenly, when I was around 16, mixed-race girls became fashionable overnight; but again, on conditions. Black women, and particularly mixed-race women, with Eurocentric features, began popping up on our tv screens, on our playlists and in magazines. Something, which I’ll refer to as the Beyoncé effect, began to spread through the cultural consciousness of white communities, particularly that of teenagers. It extended boundaries of beauty to encompass those with darker skin, but only if they had managed to defy their blackness. In other words, you could be black and beautiful, as long as you’d inherited the right combination of typically European genes. Conditions of the Beyoncé effect included things like being black, but distinctly light-skinned. Having curves, but only in the right places. Adopting European hairstyles, markedly distant from afros. Essentially being exotic but relatable. Terms like “lighty” and “mixie” began to circulate as positive ways to describe beautiful light-skinned women. However, these novel terms, like most racial semantics, are heavily loaded with negative connotations, leaving them controversial. Every one of my friends that I ask about the terms say that “lighty” is a positive descriptive word for light-skinned black and mixed-race women. Much of my socialisation with the word left me also seeing it as a positive adjective, and as a teenager, craving to be denominated as one. In 2019, the word was central to a controversial debate, with Love Island contestant Sherif Lane receiving a tirade of abuse from the British press for using the “racial slur”, as they put it. Talking about mixed-race contestant Amber Gill, he said: “‘A lighty like her would be hugely appreciated in London.” He was pulled aside by the producers and told not to use the term again. Thinking it was a London colloquialism, with negative connotations elsewhere, Lane raised the issue with Gill, who reassured him that “we use it in Newcastle all the time. I don’t think it’s offensive.” This was one of the main contributing factors that saw him axed from the show. The word itself is, in my view, undeniably positively charged in the way it has been socialised into common British lexicon. However, it is problematic in its suggestion of the selective celebration of black women. The word suggests that black culture, if diluted, is socially acceptable in communities, like those that I was a part of as a teenager. It divides black women into categories according to the white palate. The antithesis of “lighty” would be “darky”. The words, as adjectives, are identically formed. However, their connotations are dramatically different. Lane, in response to allegations of racism, said “I know you can’t call a black person a darky. So I guess lighty isn’t a good word either.” The problem here isn’t racism, its colourism. The reason these identically formed words have such different cultural connotations typifies the division of black people into categories according to preferential levels of pigmentation. This is colourism at its finest. Words that mean nothing have been socialised with colonial connotations of dark as ugly and light as beautiful, forming one into insult and the other a compliment. The amount of melanin black people inherit is therefore used to determine their aesthetic value in British society. Unfortunately for my teenage self, I quickly learnt that I fell into the category of mixed-race girls who had the great latent potential for beauty but were too deformed to actualise it. Who had inherited too much blackness to qualify for even subsidised beauty?

As a teenager, my access to, and knowledge of, communities that celebrated afro-centric features as beautiful was scarce. Once or twice a month, my dad would take me to my Nan’s house in Newham, which was the hub for close and extended family gatherings. I would marvel at my older female cousins, accepting them as both black and beautiful, but still as exceptions to the rule. Inside this nucleus of a Caribbean family, I was shown that beauty could take different forms, outside of thin, white and blonde. However, my very problematic teenage conception of beauty relied heavily on the overt validation of a person by a collective, which I didn’t see happening to the black women inside of my Nan’s house. Despite these visits, I still largely maintained my concept of white as the default. When I was about 17, one of my cousins commented that if I lived in the area I would be in no short supply of male attention. I played with the comment in my mind for years. The idea that beauty was a fluid concept, with standards only relevant to each area’s demographics, was a revelation. I slowly realised that validation could come from collectives other than white teenage girls and boys, riddled with colonially based ideals of beauty. This concept was actualised for me when I went to university in Brighton.

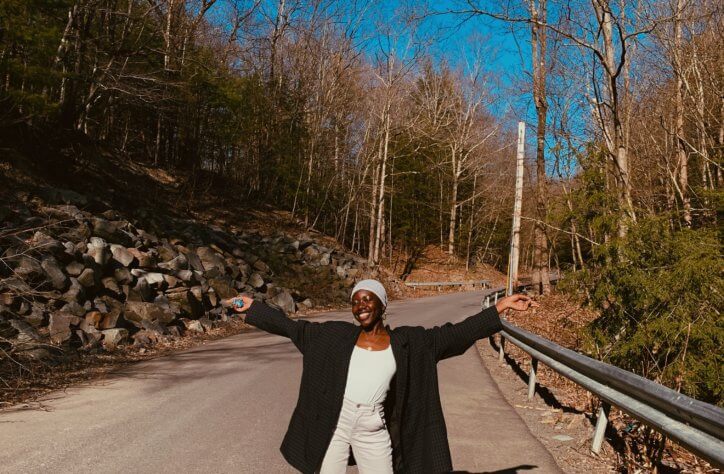

I finally saw every type of black and mixed-race girl being overtly celebrated, by men and women of all ethnicities. It gave me perspective like I’d never had. I finally realised that Bexley wasn’t, in fact, the entire world, or even a microcosm of it. Now, at the end of my degree, and my time in Brighton, I’m returning home to Bexley indefinitely. I’m now faced with the task of finding validation from within because if my journey into womanhood so far has taught me anything, it’s that you can’t rely on the opinions of others to feel beautiful.