I hold on to my ear like my life depends on it. Trembling but brave, a 100 degree hot comb inches its way to my scalp. Almost burning my bridge to beauty, but safely landing on my kinks. Oil glistens on the fingertips of Mrs. Mattie, my hairstylist, as she swoops the pink grease out of a jar , unto my jet black hair to help glide the press. I inhale slowly, trying my best not sweat, knowing that would be counterproductive to the process. “Are you ok baby?” Yes ma’am, I say praying the pretty process is soon done.

Black women learn to endure pain at an early age. Braids, pressing combs, and relaxers have for many years been apart of the black female experience. The price of entry to a white world, where beauty is European and a prerequisite for love. And though trauma is a word rarely used to describe the above experiences, as I look back I cant help to label it as so.

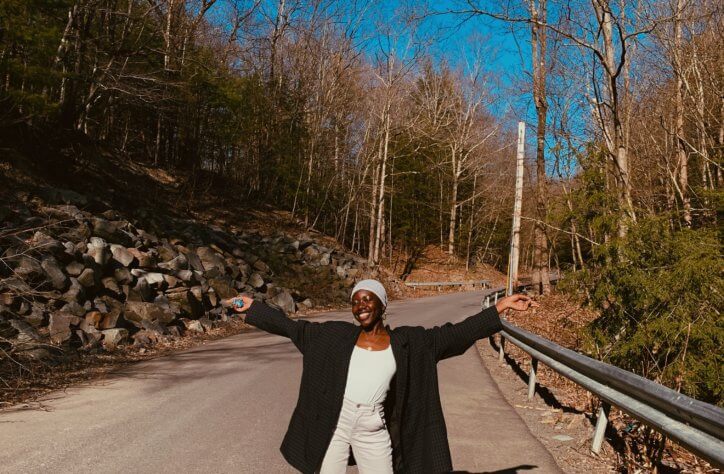

Unpacking that trauma hasn’t been easy. I recently sat in my therapy session and told her, I just don’t feel like myself when I wear a wig. She looked at me puzzled, trying to pinpoint the root of my dissatisfaction. Why was hair and identity connected ? Though the authority in my voice could have easily deceived her into believing that statement came from a woman who was assured of who she was, I knew 7 , 13, 16, 19 year old me was speaking. The little girl who wanted her ponytails stretched so the boys could pull them, and the girls could envy. The little girl who wanted her aunties to come up to her in the summer and say, “ wow baby your hair is getting so long.” The little girl who dreaded getting her ends clipped because a black girl with long hair was crowned with the golden ticket. A wig was false glory in my book, and the embarrassment of wearing hair that I couldn’t deceive as my own felt like a weakness.. Not to mention the conversation I would have to have with the guy I was dating, “ I know what this looks like, but its not mine.” Clearly, I still had work to do

I’ve always felt a quiet shame after being asked the question, “ Is that your real hair?” What’s buried beneath their curiosity ? How does knowing if my tresses are genetically supported by my ancestors, serve them? What does it confirm if I tell them no? Why does it excite them If I tell them yes? And most importantly, what does it say about me that I care? Most importantly, how do I reframe the narrative of my own beauty?

Recently I held a family member’s daughter In my arms. And before I called her smart, healthy, or strong, I called her pretty. And though the reaction was instinctive, something about being beautiful being my first thought made me challenge my way of thinking. That night, I decided to make a list of all the things I could compliment her on besides her beauty

As soon as we enter this world we are given a name we didn’t chose, and defined by an aesthetic we had nothing to do with . But as I gathered the words and hopes for my niece, I realized identity is not attached to what we have , but who we are. And even at 7 days old,I could admire the strength she shows when she lifts her tiny hand, not just the curly locs on her head. I could admire the way she sleeps peacefully in the midst of a LA noise , and call her wise not just cute. I realized I didn’t have to deny her compliments on her beauty, but I must actively refuse to define her by it. I must actively refuse to describe her with words that only scratch the surface of the woman she will one day become. And with that same daily diligence, learn to do the same for me.