My dad died a month after my tenth birthday.

And when I say he died, I mean died. He didn’t “pass on” and I didn’t “lose him” or other euphemisms. He died and it was the worst thing that ever happened to me. My memories of him and the stories I am told merge into the image I hold of him: a man with a huge smile who loved all things and people deeply, laughed all the time, lived for pleasure, was – according to my Mum – fantastically idle, and was truly loved by every person he ever encountered. A really excellent human.

Writing this now, I know I don’t want to talk about the gut-wrenching void I felt or the tears I cried. I want to talk about the reasons why I am able to acknowledge grief so fearlessly. I want to talk about how I coped.

I think I remember it so clearly: nine-year-old me sitting there at the table with my dad and my seven-year-old brother six months before he died. ‘Darlings, I have cancer,’ he said. Oh. ‘They can’t take it out.’ Oh. Later that night I lay in bed with my mum and brother. ‘Mum, is Dad going to die?’ I asked. ‘I hope not,’ she said, not quite lying but not quite telling the truth. (I later learnt that she had been advised to say that by an amazing child bereavement charity, Winston’s Wish, who she phoned now and then for support.) This initial gesture of honesty became the first of many that were a crucial part of my coping.

I understood a lot of what went on at that the time only later in my life. Back then, all I understood was that I was very sad, that I missed my dad horribly, but I was going to be OK. The way a young person copes with grief is a lot to do with how the adults in their life guide them through it. I’m pretty sure I experienced the most textbook-perfect version of bereavement I could have thanks to my mum and extended family. One of our mantras was ‘shit happens’. It sounds glib, but it was surprisingly comforting.

The main things Mum knew were that we should be swathed in love and never lied to. And that’s truly what made it manageable. This was a particularly shit thing that happened, but this wouldn’t define me or my life. All our questions were answered in terms we might understand – though obviously glossing over anything too distressing, like the physical pain Dad was in. I learnt to say goodbye and I love you to him every time I left the room in the last few weeks as he grew thinner and sicker. I knew he was going to die but I knew he didn’t want to discuss it himself, so I spoke to my mum and other members of my family instead.

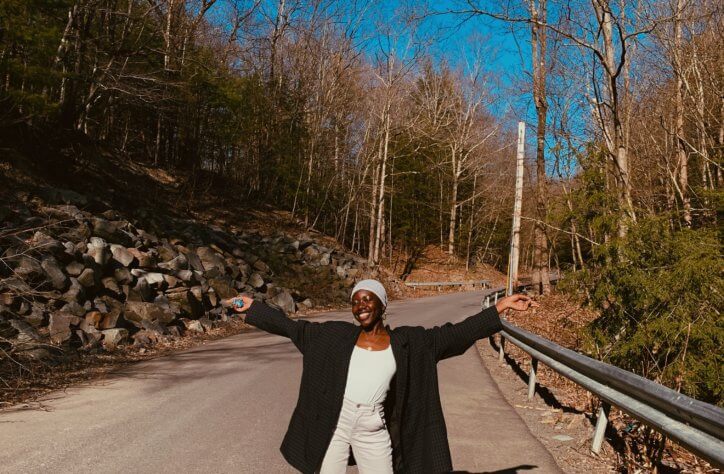

My mum, who was always an atheist, knew it would be hypocritical (and to her, a lie) to talk about heaven to us. So we found some comfort in pantheism. This was something my ancestor William Wordsworth lived by: the belief system that god and the life-force exists in all objects in nature. As he puts it in a Lucy poem, when we die, we’re all “Rolled round in earth’s diurnal course, with rocks, and stones, and trees.” My brother and I knew we had come from nature and we would return to nature. When he died, my little brother and I spent time with his body. Then my brother went and shouted ‘Bye, Dad!’ out of the open window. Even though Dad’s body was still lying on the bed, we knew his life-force had moved on, back into the air that we breathed.

That way, we never felt that he would be looking down on us (possibly disapprovingly) all our lives, but that we could still talk to him whenever we chose to. And we learnt not lie to ourselves about how we felt. You really don’t know how hard it’s going to be, so cannot truly prepare yourself. But when it comes – you must allow yourself to feel anything and everything. It’s OK to cry but it’s also OK to laugh hard. We were fully involved in the funeral preparations and I remember having a lot of fun at his wake.

So can you do bereavement well? Can you get it ‘right’? Can you grieve constructively and gently? Am I remembering it wrong? That summer was both the happiest and sunniest of my childhood, and the absolute worst time of my life. And it permanently changed everything.

Grief for me now and over the years hasn’t been constant. It has arrived in many different forms and stages throughout life. Sometimes by choice – as when I elect to be overcome by a cathartic purge on anniversaries, and sometimes not by choice – when I feel that sick feeling rise up through me that I just want to push away.

One of my coping mechanisms is to paint my grief out into beautiful images and vignettes. My youth seems like a film. Vivid and heightened, magical and dreamlike memories with a large sense of being loved. I think that’s what happens when you make more of a conscious effort to remember. Moments of pain are so palpable I can pinpoint them, and focus them into tiny magical stories.

One was the first Christmas without him. My brother, Mum and I were driving up to the countryside on a very snowy Christmas morning. On an A road, the traffic came to a halt as cars slowly veered around a dying, bright white seagull in the middle of the road, until someone stopped and gently moved it onto the verge. We pulled over and all wept and wept and sat in our shared pain.

Another was on my brother’s eighth birthday, a few months after my dad died. My dad and my little brother shared a birthday. In the card Dad wrote for my little brother to open after he died, it read, ‘I love you always, darling. You can have my birthday now, too.’

I remember the Father’s Day card I bought for Dad on the first Father’s Day after he wasn’t there. Yes, it’s an irrelevant corporate holiday, but then it was a very important part of my grief. I remember the multi-coloured helium filled balloons we sent skyward on each anniversary of his death (until we realised it wasn’t particularly environmentally friendly…). I remember the two trees, now 15 years old, that we planted with him a week before he died. Some of his ashes are scattered in the same spot. They’re now huge and bearing fruit. I remember him when I’m dancing in the kitchen with my family to Steve Harley’s ‘Come Up and See Me’, which we played at his funeral.

And then, even a few weeks ago, I felt wonderful and strange when an old friend of my dad looked into my eyes and said, ‘You know, you’re just like him.’

There’s also an unspoken connection with anyone who has lost a parent as a child. I seem to know quite a few (shit happens). There’s an unnamable bond. I don’t run away from their grief. In fact, I want to talk to people who have had people in their lives die. I want to help them share and cry and laugh and remember, the way I was helped too. Grief looks and feels different for everyone, but talking about it and about the person you miss never hurts.

That said, I found it surprisingly difficult to write this piece. I’ve had to face things I don’t really think about much anymore and that has been painful, as well as useful. And there’s also stuff that the adult me is not quite ready to talk about on a public platform!

What is certain is that the death of my wonderful dad irrevocably changed me, and my life, for good and bad. I still get assaulted by a deep, sickening pain when something suddenly reminds me of him or that time, when I think of my mum’s selflessness, or when I am reminded of how long I have not known him. But I’m also OK. I’m actually really OK. I definitely love a lot harder, try to live life fully and more deliberately, and I champion honesty, connection and laughter as remedies to pain. I do still cry at most soppy things, but apparently so did he! I was lucky to have known him and to have been loved by him. Thanks, Dad, for everything.